(You can read part one of this series here. If you’d like to download the entire series as one document, you can do so by clicking here.)

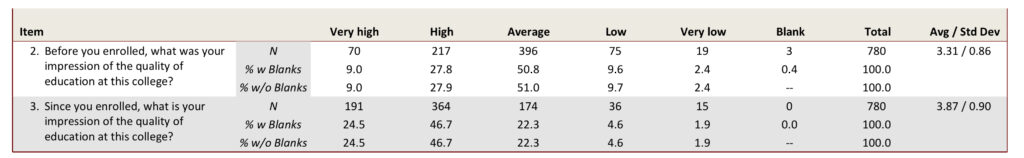

At a recent Academic Affairs meeting, Dr. John Osae-Kwapong, Associate Vice President for Institutional Effectiveness and Strategic Planning (OIESP), presented data from the SUNY Student Opinion Survey – 2019 Form B. We would like to draw your attention to items 2 and 3 from page one of the summary:

Out of the 780 students surveyed, only 70 (less than 10%) answered item 2 by saying they thought the quality of education offered at NCC was “very high” before they enrolled. In response to item 3, however, that number more than doubled, to 191 (almost 25%). Inversely, while 396 students (more than 50%) rated NCC’s quality of education as merely “average” before they enrolled, that number dropped to 174 (less than 25%), when students gave their post-enrollment assessments.

Those numbers should make every single one of us on this campus—faculty, staff, and administration—proud of the work we do here on a daily basis. We, however, the Nassau Community College Federation of Teachers, would be remiss—and, frankly, a crucially important part of the whole #EndCCStigma conversation would be left out—if we did not point out that the people on the front lines of making the difference in those numbers are our members, classroom and non-classroom, as well as the classroom and non-classroom members of the Adjunct Faculty Association (AFA). OCC’s President Robinson makes a point of acknowledging the central role faculty play, as do many of the people he speaks with on his podcast. Yet, despite the enthusiasm they express for the transformative nature of the faculty-student relationship—and we look forward to hearing how Dr. Williams addresses this in the vision statement he has promised to deliver later this academic year—the #EndCCStigma campaign itself tends to skim the surface when discussing the faculty-related issues that confronting the stigma inevitably raises.

One way of describing the hierarchy that obtains within higher education goes something like this: Four year colleges and research universities are the institutions where knowledge is created; community colleges are the institutions where it is (merely) taught. The implication, of course, one among many, is that—just like community college students were not able to make the cut at four-year institutions (which we know is often not the case)—community college faculty simply don’t measure up as researchers and scholars, and so teaching is basically all we are truly qualified to do. Indeed, many of us at NCC who do research, present at conferences, and/or publish, perform, or otherwise produce our own creative work have experienced the consequences of this implication firsthand. Condescension, rejection, dismissiveness, even outright derision are in some places still the response we get when we dare to claim we have something worthwhile, and perhaps even original, to contribute to our fields. In fact, we know of colleagues in several departments across campus who list their affiliation as “SUNY Nassau” rather than “Nassau Community College” in order to avoid the taint that the phrase “community college” is understood to carry.

Thankfully, professional associations within the academy have begun to take notice. Organizations as disparate as the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP), the Modern Language Association (MLA), the American Sociological Association (ASA), the American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB), the American Chemical Society (ACS), and the American Historical Association (AHS) have taken steps to recognize community college faculty both as scholars in our own right and as academics who offer a kind of pedagogical experience and expertise from which our disciplines as a whole, not to mention our four-year colleagues in particular, could benefit.

Ironically, this movement towards greater integration of community college faculty into the intellectual, scholarly, and pedagogical lives of our various disciplines is at odds with certain national trends in higher education, perhaps especially the ever-increasing reliance on adjunct and contingent academic labor, faculty who possess neither the protections of tenure nor the stability and benefits of full-time employment. In her article, “The Politics of Contingent Academic Labor,” Claire Goldstene argues that, because this shift to a contingent workforce eliminates tenure as a safeguard of academic freedom, what has come to be known as the adjunctification of our profession is in fact antithetical to the spirit of inquiry and discovery that informs the best research, scholarship, and teaching. As a consequence, she argues further, it undermines the democratizing and progressive potential of the work higher education, and particularly public higher education does, if by “progressive” we understand not this or that left-leaning policy, but rather making possible the increased participation of more and more different kinds of people at all levels of socioeconomic, political, cultural, and civic life.

Our next post, the longest in the series, will explore some of the implications of Goldstene’s argument a little further.

One Response

As a full-time, full professor of English for 19 years at Nassau, I am cognizant of its ‘branding’ as ‘the 13th grade.’ In fact, just a few weeks ago, I heard a young female students speaking to four other students outside South Hall, who said the following: “I used to go to a ‘real’ college, Lafayette. But now, I’m here.” Those words pierced my heart, to say the least. I debated going over to that little circle of friends to tell them that they were indeed attending the State University of New York – a prestigious university system,- and that the learning goals, objectives, and outcomes for each of their classes were just as challenging as those at Lafayette. But, rather than intrude on a conversation of which I was not a part, I thought, “Now, more than ever, the college needs to rebrand.”

Last semester, in my role as Senator at a Senate meeting, I voiced the need to ‘rebrand’ the college to avoid the community college stigma. I noted that as a campus of the State University of New York, we should rebrand to reflect that inclusion by changing the college’s name to: SUNY at Nassau, a Community College of the State University of New York. This is the title by SUNY Adirondach (a community college) is known.

I was informed by a member of the ASEC committee that I should contact the Provost to this end. In truth, however, I don’t think one lone voice is enough to accomplish the task rebranding — we need a committee to work out the details and then present them to the Provost. I am willing to give of my time and effort to achieve this goal. When students can one day look upon this amazing institution as SUNY Nassau, I think half the battle of removing the community college stigma will be won.